The Lang Collection at the Yale University Art Gallery

Franz Kline (1910-1962) Portrait of Nijinsky, 1942 Oil on canvas, 23 x 17 1/2 in.

Franz Kline’s Portrait of Nijinsky (1942) was originally part of the collection of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. The portrait is the second earliest of four known versions, three of which are similar in composition and style to the painting donated by the Friday Foundation to the Gallery. The earliest version, Nijinsky (1940), was once owned by the New York–based collector Theodore J. Edlich, Jr., and now belongs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Kline painted Large Clown (Nijinsky as Petrushka) (1948) on a commission for David Orr, one of the artist’s most supportive patrons, whose wife later donated the painting to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, in Harford, Connecticut. The fourth version, Nijinsky (1950), which now resides in the Met’s collection, is the only one that Kline executed in the non-representational and gestural mode that has come to be associated with his “mature” or “classic” style.

The three versions of the portrait from the 1940s, including the Gallery’s recently gifted Portrait of Nijinsky, are based on Elliott and Fry’s publicity photograph, from 1911, of the Polish-Russian ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky dressed as the puppet Petrushka, the lead character in one of Igor Stravinsky’s famous ballets. Several scholars have asserted that Kline identified with Petrushka, who falls in love with a ballerina but is rejected. Kline’s wife, Elizabeth Parsons, was a ballet dancer and, like Nijinsky, she suffered from schizophrenia for much of her life.

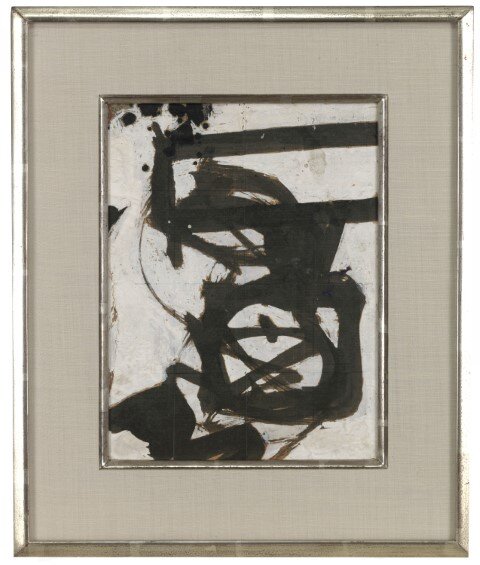

Franz Kline (1910-1962) Untitled, 1949 Ink and oil on paper, 10 1/2 x 8 1/2 in.

Kline produced Untitled (1949) in the same year that he made the transition to his “classic” black-and- white style. In the following year, he debuted his large-scale abstractions at the Charles Egan Gallery, in New York, featuring the Met’s Nijinsky (1950). Although Kline’s works from this period are often characterized as being akin to Japanese calligraphy, the artist himself resisted such comparisons to writing or symbolic characters. During this transitional period in 1949–50, his seemingly abstract paintings and works on paper initially developed from figure drawings and, in some cases, explicitly depicted human figures.

Franz Kline (1910-1962) Untitled (Study for Nijinsky), 1950 Oil, ink and cassein on board, 11 x 8 1/4 in.

Kline used Untitled (Study for Nijinsky) (1950) as the basis for the Met’s Nijinsky (1950), one of the central paintings of his black-and-white style. As with Kline’s other studies of this period, Untitled (Study for Nijinsky) is crucial to understanding the final painting. For his large-scale abstractions, Kline’s working method involved closely following the lines and forms in the sketch, even to the point of blurring hard-edged strokes to create a sketchy quality. He mimicked this sketchiness both in the painting’s areas of white paint as well as its black marks. Thus, Kline’s process was slower and more deliberate than his works’ longstanding association with the term “action painting” implies.

Franz Kline (1910-1962) Untitled, 1961 Oil and brush on paper, 18 x 18 1/4 in.

Untitled (1961) belonged to the estate of the artist before it was sold to Richard and Jane Lang by the David McKee Gallery, where it had been shown in a solo exhibition of Kline’s work in 1975. It was not until 1979, in an exhibition at the Phillips Collection, in Washington, D.C., that Kline’s abstractions in color came to be recognized as a significant body of work. Between 1950 and 1956, Kline worked primarily in black and white, employing oil and commercial enamels as his medium. After 1956, the year in which he had his first solo exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery, he began to use colored paint from tubes. This work on paper, Untitled (1961), coincides with a time which Kline had turned to working in bright color once again.

Mark Rothko (1903-1970) Untitled, 1941-1942 Oil on canvas, 32 x 36 in.

Mark Rothko’s Untitled (1941–42) is part of a large group of works made between 1941 and 1946, which is generally considered his “surrealist” period. Like Untitled, many of these works refer to subject matter related to the New Testament, such as the Crucifixion or Last Supper, and ancient myths, such as Antigone. Several paintings also share the compositional division into three “stacks,” with a top layer of interlocking faces, a middle layer of ornamental banding, and a bottom layer with human or animal limbs. Rothko explained his attraction to myth in terms of his interpretation of the philosopher

Friedrich Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy (1872), which informed Rothko’s belief that mythological figures are necessary for assuring the existence of eternal life to humankind.

Mark Rothko (1903-1970) No. 11 (Yellow, Green and Black), 1950 Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 33 3/4 in.

Before entering the collection of Richard and Jane Lang, Rothko’s No. 11 (Yellow, Green and Black) (1950) was featured in exhibitions at the Betty Parsons Gallery (1952), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1953), and the Sidney Janis Gallery (1955). No. 11 belongs to the first group of paintings now considered to represent Rothko’s mature style, which is characterized by large areas of color that have the effect of immersing viewers. With these paintings, Rothko maintained the stacked structure of his earlier “surrealist” paintings (for example, Untitled, 1941–42) to divide the composition into registers— here, filled entirely with color rather than mythological references. No. 11 is the earliest of the artist’s signature-style paintings to enter the Gallery’s collection